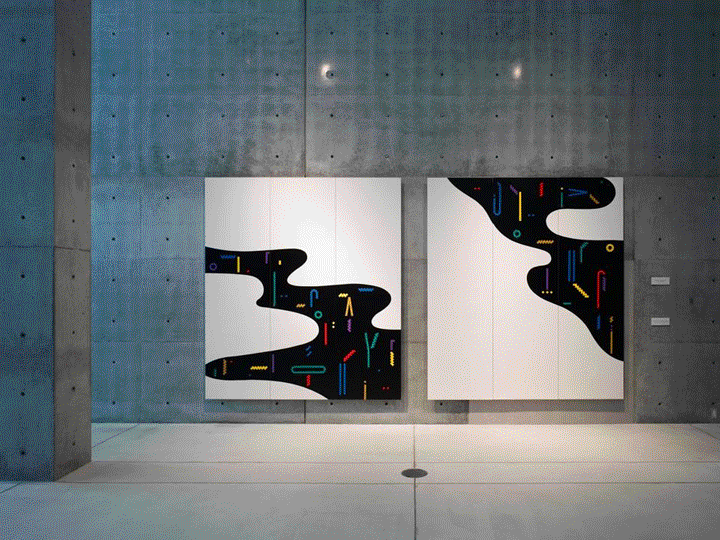

A graphic design museum

Nicola-Matteo Munari.

Piacenza, Italy. 2017

Nicola-Matteo Munari,

In 2003 Japanese couturier Issey Miyake published an article in the national newspaper Asahi Shimbun titled “Time to create a design museum” – title to which I added the word ‘graphic’ and borrowed for this text – inviting readers to think about the relevance of Japanese design and the country’s need to establish its own design museum. After fourteen years, the museum still doesn’t exist despite the joint efforts of Miyake and art historian Masanori Aoyagi, who founded together the Society for a Design Museum Japan in 2012. Facing the same issue in his “Manifesto for a 21st century design museum” (Domus 976, 2014), industrial designer Naoto Fukasawa emphasised the strangeness of that absence considering that “the Japanese are a people with boundless regard for beauty, excelling in sophisticated product making,” and that “the world has recognised these facts.”

However, if Japan’s lack of a design museum is actually strange even more strange is the absence of a graphic design museum in the whole world. An absence that seems even more serious in Italy, from where I write. Indeed, the Italian Constitution, which represents an exemplary model for “the right to culture” (Salvatore Settis), establishes that “the Republic promotes the development of culture, and the scientific and technical research. It protects the landscape, and the historic and artistic heritage of the Nation” (Italian Constitution, Art. 9). But it’s precisely in these words that is enclosed the reason of this absence. As a matter of fact, while it’s true that graphic design’s cultural relevance is universally recognised, it’s by no means its nature as cultural and artistic heritage. Indeed, not only there are no museums dedicated to graphic design, but also it’s never been proposed to consider graphic design’s production as such an heritage — a concept that is essential to understand the need for a museum dedicated to its protection and promotion.

Actually, there are important design museums that also exhibit graphic design. For example, Triennale Design Museum in Milan, that however dedicated only one show in ten years to graphic design, whose presence and function is generally that of supporting the communication of something else. Also in Italy there is the Istituto Centrale per la Grafica (Central Institute for the Graphics) which however, completely ignores graphic design from its interests, limiting the tutelage to graphics artistic expressions such as historic prints and drawings. At least one museum, even if not being exclusively dedicated to graphic design, deserved to be mentioned as a good example. It’s the Museum für Gestaltung of Zurich that gives to graphic design an importance not only equal but perhaps greater to that given to other design expressions. But it’s a special museum, whose name is particularly evocative of visual communication, based in a special country, Switzerland, which is an historic champion of graphic design.

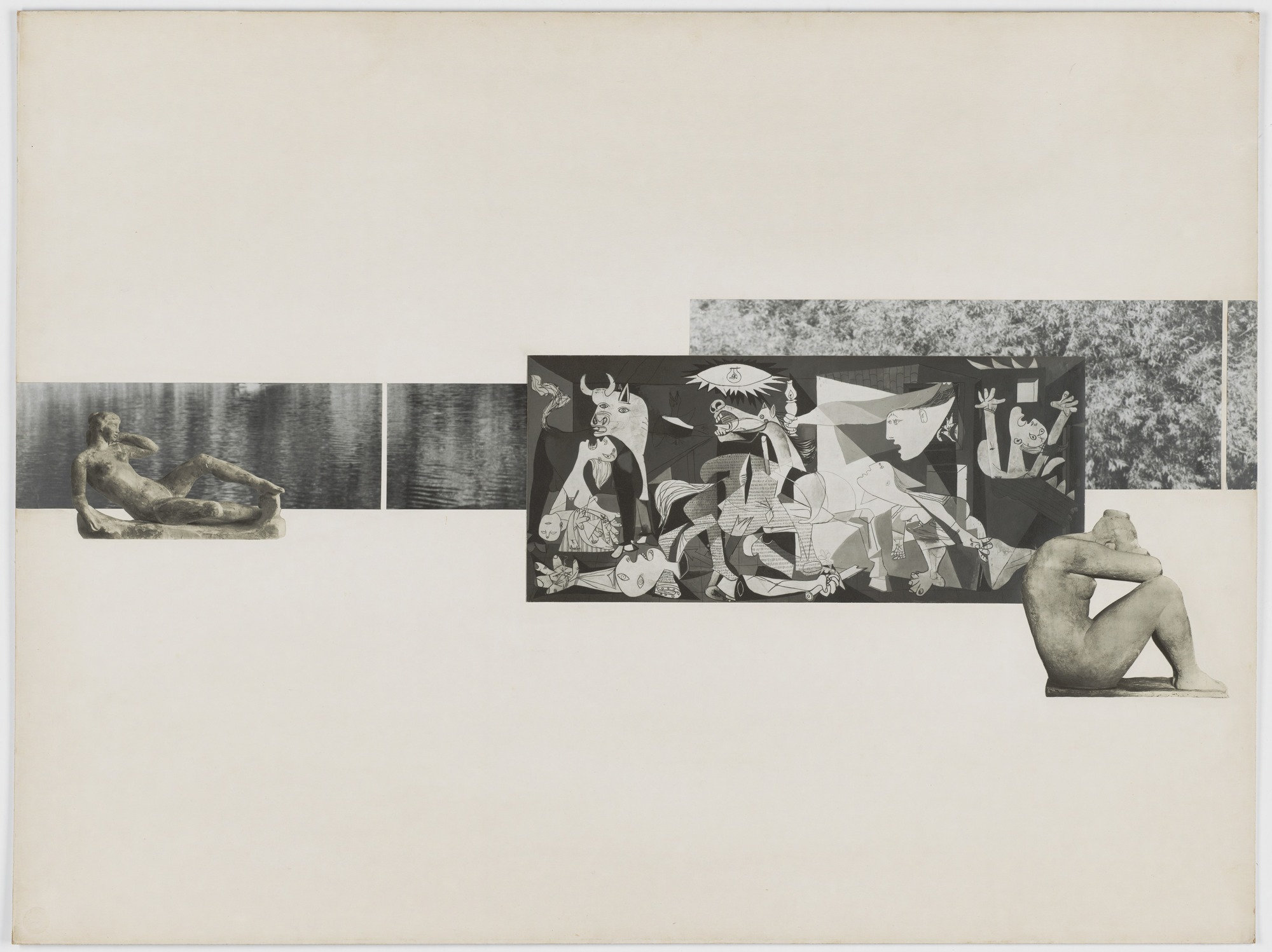

Of course graphic design is not conceived to be Art – at least according to the elite conception commonly attributed to the word – even if we could consider it as a form of socially useful art. And it’s also true that lacking an artistic intentionality and claim, graphic design is not exhibited in galleries and sold at exorbitant prices thus arousing amazement and admiration. On the contrary, it silently accompanies us in our everyday life becoming an integral part of it. And yet, it’s also true that graphic design gains great artistic value in its own actualisation. Indeed, once completed, the design becomes an artefact. It’s therefore incomprehensible the still widespread diffidence of considering graphic design as something worthy of protection and artistically important as much as those works which are the product of an art conception belonging to a world where design didn’t exist. A century has passed since the advent of design and it’s now evident the absurdity of such a mistrust.

In the contemporary society graphic design is more important than ever. IT tools increased communication between peoples and determined the need for improving the quality of the communication itself, while digital devices gave typography a renewed role and functionality. Design can only adapt to these changes, indeed as Naoto Fukasawa pointed out in the aforementioned manifesto, “the concept that defines design as form, looks, colour, and decoration have started to change. While function remains an important factor, people are discussing form less and less, and instead exploring how something can be designed to build relationships between things and people or between things and things. This can be described as design for communication.” The word ‘design’ itself is today associated in the world more closely to graphics than to furniture, fashion, or else as recently illustrated in an article 1 published in La Lettura (supplement of the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera). And a final confirmation of this shift from products to graphics is obvious if we think that everyone in the world perfectly knows Apple’s symbol – including those who have never bought one of its products – while not so many people knows the various computers that it produced over time or simply the full range of its products today on the market.

To my extent, I am trying to promote the cultural relevance of graphic design through the publication of Designculture since 2013 and that of Archivio Grafica Italiana since 2015, which even more expressly tries to propose graphic design as cultural and artistic heritage, thus overcoming the lack of a real museum with a digital one. I think that graphic design can actually contribute to make the world a modern world, a concept that expresses the very vision of a better future. An aspiration, that to modernity, which is today greatly lost and perhaps unattainable, and yet this is why it’s even more necessary. If we don’t want to loose this heritage and develop it in a constructive perspective, the need for such a museum is increasingly urgent because to build a better future we need to know our past, and without a past we are condemned to live in the uncertainty and instability of a constant present.

As Japanese graphic designer Ikko Tanaka has been quoted in the article by Miyake, “designers feel compelled to continuously explore new directions, but if they face only forward, they have no baseline for comparisons.”