The death of critical thinking

Michael Klein,

From the editor's desk

There is not enough talking about design. This seemingly paradoxical statement is nonetheless a fact. There is no shortage of cocktail party talk on design, or of resources concerned exclusively with spreading fashionable and critical-free content; however, serious criticism is alarmingly absent. There is not enough talking either about good design or bad design in a critical way — the only way that fosters a debate between designers, as well as giving a truly positive contribution to the discipline.

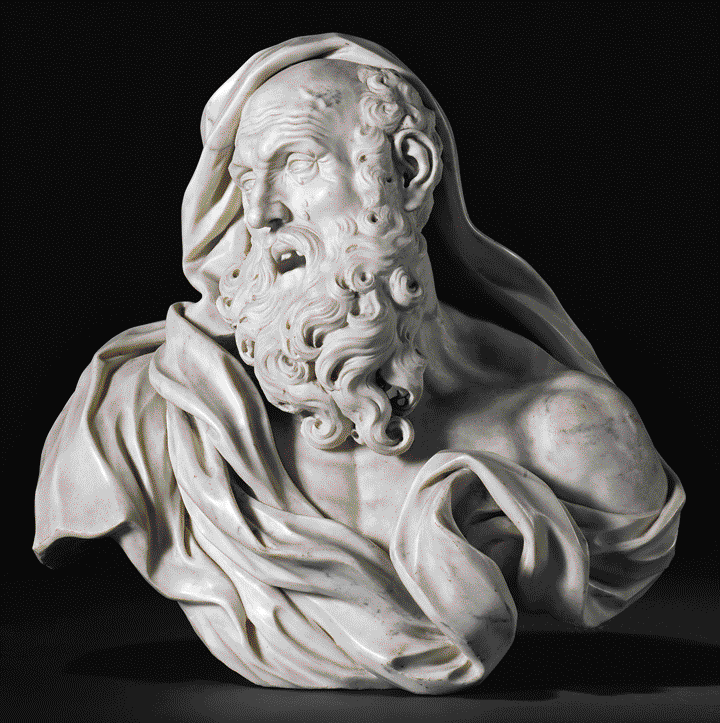

This problem hasn't gone completely unnoticed. In our third issue, famed design critic Adrian Shaughnessy affirms: «Graphic design criticism is in the deep freeze». 1 Three years ago, Meydad Marzan, currently a designer at Google, complained about the death of critical thinking in industrial design. 2 In his article, Marzan cites Ayn Rand to raise some fundamental issues such as conflict seen as the driving force for progress, or the need to position oneself forcefully – with clear opinions – within the design debate. This truth was already grasped by the Greek philosopher Heraclitus over 2500 years ago. As a matter of fact, according to Heraclitus, conflict rules everything that happens in the universe — the end of a continuous tension between opposites (coincidentia oppositorum) would mean the end of the world.

If this seemed clear to Heraclitus it doesn't seem so clear in our time, a time in which forty years of postmodern culture and a recent series of catastrophic economic and societal events have led to a profound change in the way people think. Stripped of any kind of certainty, people couldn't help but getting dragged into an overwhelming anarchy of overlapping voices — one in which critical thinking is abolished, taking a stand is seen as an impediment to a distorted notion of freedom, and the idea that there is no right or wrong has become ubiquitous in the arts.

It is thus necessary to get back to talking about design. It is imperative to do so with a critical voice, by taking a stand. This is why we have founded this publication, with an editorial line that is concerned with the issues discussed so far. With this renewed consciousness we then propose to establish some key points in order to try and start a more meaningful discussion around design.

First and foremost, it is necessary to reject the idea that there is no right or wrong when it comes to design. There are better ways to design than others, and completely wrong ways to do so. Modernist culture has established the fundamental principles of good design. The cultural and social commitment of design, the search for universal solutions, the idea of reaching the essence of things with economy of means, the debate over the relationship between form and function and the idea of inclusive design are only but a few of these principles. Over the last century, pioneers such as Mies van der Rohe, Max Bill, Jan Tchichold and later generations of designers such as Craig Ellwood, Charles and Ray Eames, Massimo Vignelli, Paul Rand and many others gave their creative contribution to the best expression of these ideas. They worked to establish design's recognition as an integral part of the development of society — a discipline that is profoundly integrated in our culture.

The postmodern period that followed has instead tried to discard everything that was done before. Although it was born from the culturally sincere intentions of some architects and designers, it quickly degenerated into the exaggeration of an anarchic and self-referential creativity, as well as in the figure of an artist-designer more focused on not being "boring" than on producing something of value.

We strongly reject such a vision of design. Not only does it undermine the profession but it reduces it to a mere self-expression tool — something destined to produce useless artefacts born out of selfishness.

Secondly, we believe that good design is always the result of a structured thought that starts from the a problem to reach an authentic solution. This is almost never possible if one follows fashions instead of following thought. With this we don't mean to deny the importance of being aware of the status quo of design, or of other designers' work; rather, we mean that excellent projects can only arise from independent, coherent thought protracted over time. There are no easy shortcuts.

What we described so far is part of the ideological apparatus that lays the foundation of this publication, as well as our criteria in choosing themes, interviews and projects. Not everyone will agree with us, and that is a positive thing to keep an open and lively dialogue. Whatever the opinions, however, one has to think critically and be in charge of their own positions.

The death of critical thinking is the death of design.

-

1

Unit Editions, profile on Gute Process Issue 03.

↩︎ -

2

"Industrial designers, fight!" on Medium (medium.com)

↩︎